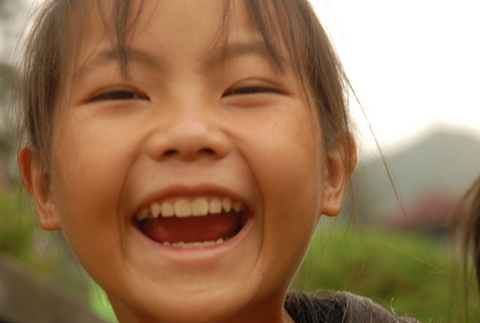

“We are not here for a long time. We are here for a good time,” laughed Meaning, a twelve-year old survivor wearing a ragged Beware of Land Mines skull and crossbones t-shirt and prosthesis leg scampering a random life pattern across fields near a stilted bamboo home in Cambodia.

“Are you with us?” pleaded a landmine child survivor removing shrapnel with an old rusty saw after stepping in heavy invisible shit, “or are you against us?”

She’s been turned out and turned down faster than a housekeeper ironing imported Egyptian threaded 400-count linen. No lye.

The thermostat of her short sweet life seeks more wattage. She faces a severe energy shortage if she doesn’t find food.

She’s one of 26,000 men women and children maimed or killed every year by land mines from forgotten conflicts. Reports from the killing fields indicate 110 million land mines lie buried in 68 countries.

It costs $3.00 to bury a landmine.

It costs $300-$900 to remove a mine. It will cost $33 billion to remove them. It will take 1,100 years. Governments spend $200-$300 million a year to detect and remove 10,000 mines. Cambodia, Angola, Afghanistan and Laos are the most heavily mined countries in the world.

40% of all land in Cambodia and 90% in Angola go unused because of land mines. One in 236 Cambodians is an amputee.

*

Expanding her awareness of mankind’s genetic stupidity, Lucky showed Zeynep a Laos map illustrating Never-Never Land.

Lao Please Don’t Rush is the most heavily bombed country in history.

25% of villages in Laos are contaminated with UXO.

Upwards of 30% of the bombs dropped on Laos failed to detonate.

80 million unexploded bombs remain in Laos.

More than half of the UXO victims are children.

*

Meaning hears children crying as doctors struggle to remove metal from her skin. She cannot raise her hands to cover her ears. Perpetual crying penetrates her heart. Tears of blood soak her skin.

The technical mine that took her right leg away one fateful day as she played near village rice paddies expanded outward at 7,000 meters per second. Ball bearings shredded everything around her heart-mind.

It may have been an American made M16A1, shallow curved with a 60-degree fan shaped pattern. The lethal range was 328 feet. Or maybe it was a plastic Russian PMN-2 disguised as a toy. She never saw it coming after stepping on the pressure plate.

Fortunately or unfortunately she didn’t die of shock and blood loss. A stranger stopped the bleeding, checked her pulse and injected her with 200cc of morphine. Strangers in a strange land carried morphine.

*

Cut the heavy deep and real shit, said a female Banlung shaman.

Fear is a tough sell unless it’s done well, well done, marinated, broiled, stir-fried, over easy, or scrambled.

Fear is blissful ignorance.

*

Meanwhile, the 1st International Beggar Conference convened in Toothpick, a wasteland near Bright Hope - a rusting rustic dream of exploratory ways and means with scientific cause and effect and logical rational certainty.

It was chaired by a distinguished group of Cambodian orphans.

NGO Fascists rented 12,000 orphans out to fake humanitarian organizations. Abandoned youth pleaded with ill-informed rich donors for marketing and branding money to feed international guilt and shame.

“Let’s eat,” said a fat banker moments before his yacht hit an iceberg in 2008.

“What you don’t see is fascinating,” said Zeynep, “like roots below the surface of appearances.”

“We have so much ice and they have so little,” said an Icelandic chess player attacking Death.

“Everyone comes to me. My patience is infinite,” said Death. “I make only one move and it’s always the correct one.”

Beggars, landmine victims, genocide survivors and sick and tired dehydrated dying starving neglected humans from 195 countries convened in sequestered committee rooms filled with suits, scholars, academics, UN personnel, CIA analysts, NGO profit motivated scam reps, IMF bankers and plastic ornamental steering mechanisms.

“We agree to disagree,” said Rich Suit.

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend,” said Wage Slave.

Orphans, beggars and children spoke about slave labor, hunger, exploitation, corruption, human trafficking, corrupt police states and the terrorism of economic poverty.

“Bad luck,” said a rich slave. “That’s a you problem, not a my problem.”

Children addressing global media held press conferences focusing jaundiced eyes on lenses, recorders and bleeding pens. Their pleas fell on deaf ears. Sound bites sang starvation’s misery.

If it bleeds it leads.

Incoming! Bleeding hearts ran for cover.

Orphan motions for adjudication, arbitration, fairness, equality and equity were tabled for further deliberation and discussion nowadays.

The average monthly wage was $37 in a Bangladesh clothing factory.

350,000 Cambodian women making $61/month stitched garments for Korean export companies.

Give someone a sewing machine and with a little luck they’ll feed their family.

Let’s Eat.

Weaving A Life, Volume 1

Share Article

Share Article